Documenting Manzanar: Exploring the World War II prison camp through the images of Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange and Toyo Miyatake

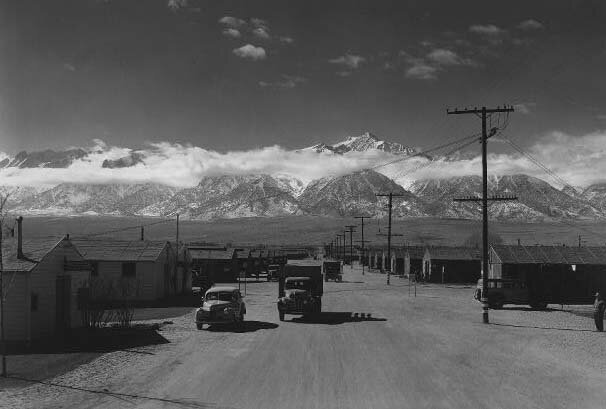

Ansel Adams's 1943 Manzanar winter street scene shows both the desolation and the beauty of the concentration camp. (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

I first learned that Ansel Adams had published a book of photos of the World War II Japanese prison camp Manzanar from my Uncle George, our family’s unofficial historian. I had sent him a Wilderness Society booklet on the great nature photographer, and in his e-mail response my uncle wrote, “Ansel Adams was not only a famous photographer and environmentalist but also a great humanitarian. He did much to document internees for posterity when it was very unpopular to do so.” Attached was a portion of Uncle George’s memoirs describing his wartime imprisonment in Manzanar, which began, “The whole of Manzanar was astir with the news that Ansel Adams would be paying a visit to our dusty and forlorn camp. His fame had preceded him even to this barren outpost.”

This tantalizing tidbit of information—that the great photographer of Yosemite and the West had documented the concentration camp—was to lead me to explore the photographic record of Manzanar, including works by Dorothea Lange and an extensive trove of images made by the Japanese photographer and prison camp inmate Toyo Miyatake. The process of peeling back the layers of meaning hidden in those photographs was also a way into my own family’s imprisonment during World War II, and it raised the question: Why was it that I knew so little about this history?

Executive Order 9066

The town of Manzanar was a dusty, hardscrabble patch of desert 230 miles northeast of Los Angeles in the once-fertile Owens Valley, flanked to the west by the majestic Sierra Nevada Mountains and to the east by the Inyo and White Mountain ranges. Its name was taken from the Spanish word for “apple orchard,” reflecting the abundant fruit ranches of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that had disappeared aseconomic success. Japanese comprised only one percent of California’s population, yet thanks to their hard work and long tradition of tilling the land, produced close to half the fruits and vegetables raised in the state.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, establishing military areas along the West Coast from which all aliens would be excluded. It became clear that “enemy aliens” included Nisei, the American-born sons and daughters of Japanese immigrants. Although Executive Order 9066 ostensibly included Italian and German nationals as well, only the Japanese were rounded up en masse and imprisoned. “Evacuation” began, the forced transport of 110,000 prisoners to 10 euphemistically named “internment camps” scattered throughout the western interior of the U.S. and operated from 1942 to 1945. The suddenness of the removal orders created chaos and panic among the Japanese community. In many cases families had only a few days to dispose of all their worldly goods, falling prey to unscrupulous bargain hunters. They lost farms, homes, pets, and cherished belongings.

The rabid anti-Japanese sentiment and the incarceration of an entire community was the result of fear of the most heedless kind; not a single Issei or Japanese American was convicted of sabotage or espionage during the entire war. A detailed February 1941 State Department report on the loyalty of Japanese residents of Hawaii and the West Coast, not released until after the war, found “a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group.” The President and the military had access to this information, yet still imprisoned the Japanese in concentration camps. As their parents languished in the camps, the combined 4,000 strong, all-volunteer Japanese American 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat team became the most decorated regiment of the war for its valor in campaigns in Italy and France.

Well-dressed farm families board evacuation buses, knowing little about their destination or the conditions they will face. Photograph by Dorothea Lange, May 1942. (Source: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley)

Prison Camp Life

Unaware of the suppressed State Department report, my father and his family obeyed orders, disposed of their belongings, dressed up in their best clothes and showed up on time at the Venice Japanese Community Center to board one in a convoy of buses that took them to Manzanar. My uncle wrote in his memoir, “Except for squalling babes and small, frightened, whimpering children, everyone rode in stoic silence. All knew that this was not a joyful holiday excursion. No one could predict what was in store for us.” When they reached their destination, they were greeted by a biting wind, dust, flimsy tar-paper covered barracks furnished only with canvas cots, bare light bulbs and crude outhouse facilities. The barracks had no running water.

The first-generation immigrant Issei, their descendents often say, endured for the sake of their children. Beneath the Japanese stoicism, however, lay a simmering anger that occasionally flared. Divisions arose among the internees between Nisei and angrier Issei and Kibei, those born in the United States but educated in Japan before returning to America. The prison camps’ primitive conditions and corruption among some camp administrators stoked the resentment of the Issei and Kibei factions. The Nisei, meanwhile, wanted desperately to prove their loyalty to America, and struggled to retain ties with their friends and teachers at home.

Uncle George maintained connections with his school, Santa Monica High, and invited his Spanish teacher and his civics teacher for a meal in the mess hall where he served as chief morning cook. George’s physics teacher read his letters aloud to the class. His principal even mailed diplomas to seniors scheduled to graduate. My uncle considered this a triumph since many other California high schools denied diplomas to their incarcerated seniors. Uncle George’s tireless letter writing paid off: his football and track coach mailed him athletic letters earned by student athletes. “I had the privilege of giving them out to my teammates at Manzanar,” Uncle George wrote.

Friction between Nisei and the Kibei-led faction led to the Manzanar riot of December 1942, in which two inmates were killed by sentries and ten wounded. A month later, camp inmates gained a system of self-government after negotiating with authorities, and conditions at the prison camp gradually improved.

End of Part 1 of 18 installments.

Read it at DiscoverNikkei.com

Read Parts 2 through 18