Union Square Far East

Roppongi, Tokyo—Michael Romano, director of culinary development for Union Square Hospitality Group, can usually be found at the company’s headquarters on Union Square East, working on special projects or roaming the kitchens of one of USHG’s many Manhattan restaurants, from North End Grill at Battery Park to the Modern in Midtown. Having served as executive chef of Union Square Café from 1988 to 2007, he is the group’s wise elder or emeritus cook and looks the part, too, wearing a thoughtful expression and tortoise-shell glasses.

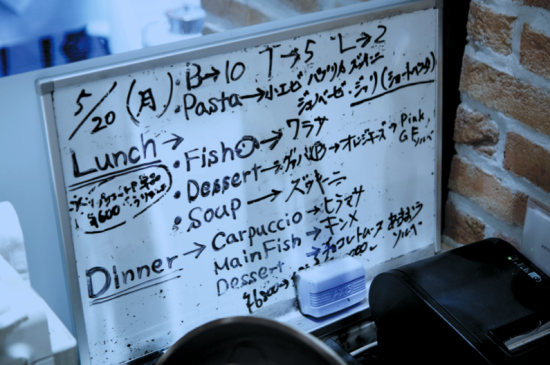

But a recent day found Romano on the other side of the globe, planning dishes for a special seven-course tasting menu with Yoshichika Matsuda, head chef of Union Square Tokyo. “Now is the season for takenoko [bamboo shoots],” says Romano, who usually does at least two of these Tokyo dinners a year. “We can cook, slice and brown them, sauté foie gras and serve it with a mostarda of orange marmalade.”

He muses on kuruma ebi (tiger prawn) risotto; veal prepared with grapes, turnips and greens, and asks, “Ima carciofi arimasuka?” (Do we have artichokes?).”

“Yes,” replies Matsuda, “but not from Japan. Not so good.”

Romano, who cultivates passions for bespoke kimono, kabuki and serious sushi, visits Tokyo several times a year to check in on USHG’s only Japanese alliance, the result of a licensing agreement that restaurateur Danny Meyer and his USHG partners, including Romano, entered into over six years ago. The idea was to create a Tokyo version of USHG’s iconic Union Square Café, which Meyer opened in 1985 as a 27-year-old greenhorn from St. Louis.

Meyer went on to build the powerhouse USHG on the strength of his restaurants’ great food and off-the-charts service. This “empire of niceness,” as New York magazine described it, now includes Gramercy Tavern, Maialino, Blue Smoke and the mushrooming burger chain Shake Shack.

Famous for his very American brand of customer service, Meyer invented an algebra of hospitality that goes far beyond perpetually filled water glasses and an ever-ready smile for guests. In his restaurant-memoir-cum-management-handbook Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business, Meyer considers every value from the metaphorical “hug” that comes with a serving of food to the importance of servers “turning over rocks” to find a hidden bond that they share with guests, whether it’s an alma mater or a hometown.

Examples of superhuman hospitality abound in USHG lore, such as the Eleven Madison Park (which Meyer sold in 2011) maître d’ who saved the anniversary celebration of two guests by taking a cab to their apartment and transferring a bottle of Champagne from freezer to refrigerator before it exploded.

When the Union Square Tokyo deal was struck, though, some observers may have wondered if a Japanese Union Square Café would succeed. Would the relaxed, familiar USC style of service clash with the more formal, ritualistic Japanese restaurant tradition? Although USHG has successfully cloned Shake Shacks around the nation and in nine international locations, exporting cheeseburgers and milkshakes is by far the safer bet. Like the international Hollywood blockbuster, the Shake Shack concept is entertainment reduced to its most sure-fire, universally appealing basics.

By contrast none of the more fine-dining establishments in USHG had yet made the leap overseas. And while Japanese diners have demonstrated deep interest in French haute cuisine and straightforward Italian, it was by no means clear that the hard-to-categorize offerings and more casual style of Union Square Café—part Berkeley casual, part Roman trattoria and part Parisian chic—would hit the sweet spot that other imports to Japan such as Michel Troisgros or Il Mulino have.

The venture called for a cross-cultural mind-meld, illustrated in a story Romano tells: One day, he happened to walk by Union Square Tokyo’s private dining room, where a strange sight caught his eye. There, at the staff’s usual pre-meal meeting, “Everyone was standing in a circle with their hands over their mouths, kind of looking at each other,” he recalls. Their eyes didn’t express shock, or dismay, though; waitstaff members were practicing a technique called “smiling with your eyes.” On an earlier visit to Tokyo, Meyer “had left that little kernel,” explains Romano. The staff was earnestly making it their own.

Since opening in 2007 Union Square Tokyo has developed its own identity, grafting the smiling-eyes and hug-like dining experience onto Japan’s already high level of service. UST’s genetic inheritance is evident in the burgundy-and-white striped shirts servers wear, a takeoff on the original striped Brooks Brothers shirts of Union Square Café servers, and in certain classic USC menu items: the bibb and red oak lettuce salad with grated Gruyère and garlic croutons and the smoked-then-grilled sirloin steak with mashed potatoes and watercress salad.

Other menu items the Americans thought would be a natural fit in Japan, though, fell flat. One “emblematic example,” says Romano, was Union Square Café’s filet mignon of tuna, which the restaurant has had on the menu since the ’80s. Cut to resemble a filet mignon, it is marinated in soy, ginger and scallion, grilled and served rare, with gari (pickled ginger) on top, wasabi mashed potatoes and a mélange of stir-fried Chinese-style vegetables.

“We thought this was going to be a slam dunk, very popular, but nobody liked it,” recalls Romano. “People were put off by the size of it—one time a table asked for it to be split nine ways.” Another problem was that the combination of ingredients, albeit all Asian, was strange to Japanese diners, who wondered: Who puts gari on cooked tuna?

“It was a lesson,” says Romano.

Another USC menu staple found success in Tokyo, but only after undergoing a drastic makeover. The popular UST hamburger, mixed with egg, milk, ketchup and panko bread crumbs, resembles meatloaf more than the all-beef Union Square Café burger simply seasoned with salt and pepper. Meanwhile, a dish original to Tokyo, the UST chef’s salad, has become a house institution: a mound of mixed greens topped with 12 kinds of vegetables, grilled chicken and shrimp, bacon, boiled eggs and cheese tossed with vinaigrette and served with a choice of thousand island or sour cream dressing.

While American diners might see this everything-but-the-kitchen sink salad as overkill, it appeals to the Japanese love of variety, and the belief that eating many different kinds of food in one day is healthful; the dish is the salad analogue of chirashizushi (sushi rice with a variety of ingredients scattered on top). Over 70 percent of lunch guests order it, making it the best-selling dish on the menu.

The desserts, such as the mascarpone cheese frozen crema catalana with orange sauce, by contrast, are half the size of American desserts.

There were non-menu hurdles to overcome, too, like the standoff over kitchen protocol. The Japanese team “designed the kitchen, and we brought in our menu,” says Romano. “There was a moment when it came down to ‘how do we execute this food, how do we make it work?’ I had my way of setting up a station and they had their way.”

The sticking points seemed minor: how to handle mise en place, the organization of each chef’s station, the logistics of calling out and handling orders. Things were heading toward a clash, so he brought in Union Square Café executive chef Carmen Quagliata, their counterpart in New York, who, Romano hoped, might be more persuasive.

The language barrier didn’t make things any easier, though. Romano spoke only a little Japanese at that point and the staff spoke only a little English.

“When you’re in the heat of action . . . sometimes I didn’t even know whether I was speaking Japanese, French, Italian or English because your mind is going so fast and your mouth can’t follow. In the end,” says Romano, “I had to let go and go with the flow because it was leading to too much trouble. Lo and behold, they got it together and they pulled it off. But letting go was hard, and it was so symbolic, in a way, of our very different cultures.”

Appropriately enough, the man who oversees this unique East-West culinary blend is himself a hybrid of the two cultures. Romano—who trained in the classical French tradition, worked at two- and three-star restaurants in Europe and helmed the kitchen at La Caravelle before joining Union Square Café—is also a Japanophile whose own passion for the country helped bring UST into being. One example of his engagement with the culture: he routinely orders up custom-made kimono, hakama and obi (the traditional Japanese robe, men’s divided skirt and sash), which he wears on theater outings and walks in the city.

In Tokyo, Romano will divide his time between menu planning and catching up with UST staff; seeing his Tokyo-based Japanese girlfriend, translator Mari Takeuchi; visiting his kimono maker and sushi chef friends; and going to the newly renovated kabuki theater in Tokyo’s Ginza district. As a supporter of Tōshō-gū, the family shrine of the Tokugawa clan that ruled Japan for over two-and-a-half centuries, he’s just returned from the shrine complex, a prized national cultural treasure. There, dressed in Edo-period garb used for ceremonial or court appearances, he rode on horseback and witnessed a display of the centuries-old tradition of yabusame, or horseback archery.

Romano’s ties to the shrine, founded in 1617, have given him rare access to its inner sanctum, and to other ceremonies that commoners rarely get to see. He relishes annual trips to “an incredibly beautiful ceremony at dawn on the first day of the year,” to witness the blessing of food in a ritual involving a whole wild hare, fish, sake and mochi (sticky rice cakes). Like other foreigners enamored with the ancient ways of the culture, he’s more appreciative and in awe of it than many Japanese are themselves.

Located in a $3 billion luxe office/hotel/retail/residential complex called Midtown Tokyo that boasts 20,000 employees, Union Square Tokyo caters to a mix of American expats and other foreigners and ladies who lunch after visits to the Suntory or 21_21 Design Sight museums. With its brick walls, hardwood floors, wine racks, Japanese-influenced floral paintings by American artist Robert Kushner (whose work also graces the walls of Union Square Café), and sunlit terrace facing a verdant greenbelt, the 120-seat restaurant could be in the Napa Valley.

Although USHG had been approached earlier about opening a Tokyo outpost, nothing had seemed like the right fit until a Japanese restaurant group called Wondertable called on Meyer. Wondertable had already secured its prime spot in Tokyo Midtown when Romano traveled to Japan in 2005 with several of his USHG partners to check it out.

Romano first visited the country in 1983 as part of a cooking competition contingent from the two-star Zurich restaurant Chez Max, where he was chef de cuisine. “It was my first taste of Japan, and I was just smitten,” Romano recalls. “It was so many different things, a bombardment of the senses, the people, the food, the culture.”

In 2004, his interest was rekindled when he spent a week cooking at an event in Nagoya. He managed to squeeze in a trip to Kyoto, but wanted more.

Just a year later, Wondertable’s overture came at the right moment. Romano and his partners were impressed with the company’s approximately 60 restaurants—not fine-dining establishments, but well-run mid-level restaurants ranging from the Italian mozzarella bar Obika to a string of shabu-shabu restaurants.

“That’s when my desire to be in Japan became an influence,” says Romano, who advocated for the licensing arrangement. “I did put in an effort to convince everyone this was a good idea, which I truly believed, knowing I’d be the one to go repeatedly to Tokyo to work at the restaurant. It was a wonderful dovetailing of interests, a win-win situation.” As executive chef of UST, he approved the selection of chef Matsuda and general manager Hidekazu Aoyagi and says of the staff at UST, “It’s like family now.”

Matsuda, 41, credits Romano with elevating the level of his own cooking and liberating his way of thinking. While Japanese tend to stick to the letter of culinary traditions, he learned from Romano that the only rule is to make things delicious, an approach that gives him permission to use miso or soy sauce in Italian dishes, to mix genres and ingredients.

For Japanese diners, he says, UST’s challenge is to change their perception of American food as being heavy, unsubtle food served in overly large portions. While the Japanese think of Italian and French food as “beautiful, healthy and delicious,” the image of American food, he notes, “is not good,” adding, “Our job is to show that’s not true.”

Like Matsuda, the rest of the staff is committed to creating a new Japanese–Union Square Café culture that combines the best of both worlds. Maître d’ Takenori Nakazato, a former chef who translated the USHG employee manual into Japanese, notes that Meyer’s best-selling Setting the Table has also been translated, as Omotenashi no Tensai, or “Genius of Hospitality.” The Danny Meyer approach that the staff at UST most wants to incorporate, says Nakazato is the idea of being “friendly but shikkari [steady, reliable or of firm character]” in equal measure, adding of Romano and Meyer’s approach: “Their philosophy has become our philosophy.”

As cooks complete the last afternoon orders and prepare for evening service, Romano weaves the tight aisles between the small pasta and fish stations and the large grill that sees heavy chicken and shrimp action at lunch for that chef’s salad. One smashes cooked lobster and extracts its meat for the popular sandwich with onion, mayonnaise and chili peppers. Yoshikazu Kondo, renowned for his skill as a fish butcher, sautés sea scallops, to be served with snow peas and a green pea sauce.

“There are no pot washers here,” Romano points out; cooks share this duty themselves.

Just before dinner service, server Michiyo Tokunaga leads a rhyming cheer, “Oishii, tanoshii, ureshii, UST!!!” (“Delicious, fun, happy, UST!!!), and a shout of approval goes up. The cheer itself, and the person leading it changes every night, says the petite and fast-moving Tokunaga, but “we all put our feeling into it.”

A day after his menu-planning session with Matsuda, Romano is in the kitchen testing recipes for his tasting menu. He’s come up with a three-part amuse-bouche, he says, including a trompe l’oeil parboiled-then-deep-fried calamari-shape pasta, stuffed with ratatouille and pesto.

“One of the things I love about being here,” says Romano, “is actually being in the kitchen, hands-on.” Next up, suika-tataki, a mix of exquisite Furuno beef tartare, finely diced watermelon, white miso, balsamic vinegar and chives, all lightly seared.

When his recipe development is done for the day, he and Takeuchi, dressed in an elegant seafoam-color kimono and a floral-pattern obi, take a taxi to see one of his kimono makers, a fifth-generation craftsman named Kanji Nakashima, whose small atelier is located in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. Ever since he was a boy growing up in New York City, driving his mother crazy over his pickiness about clothes, Romano has been interested in fashion. His love of kimono dates back to his first trip to Japan in 1983. Romano remembers admiring a formal kimono bearing a family crest in a store window and vowing that one day he would wear one.

Nakashima has altered two kimono for Romano and one for Takeuchi. After putting on a kimono in a rich shade of gray, Romano tries a new obi, tying it with the ease of a man who knows his way around traditional Japanese formal attire. He bought his first kimono in 2008 and now owns between two and three dozen—so many that Nakashima has devoted one tansu, or set of drawers, to store some of the robes for his prized American client.

Nakashima takes out a haori whose lining Romano designed himself. On the right-hand sleeve an image of the Statue of Liberty rises above a roiling sea, whose vivid blue and white curls evoke the famous Japanese woodblock artist Hokusai. On the other is the image of the legendary 17th-century swordsman and duelist Musashi Miyamoto, hands gripping his sword above his head, peering into the rough sea toward a giant whale that swims toward New York. Romano’s initials, “MPR,” are sprinkled over Miyamoto’s hakama, Nakashima points out, proudly turning over the jacket to show a stylized “MR” embroidered in white just below the collar—his own family crest. Just as Edo-period dandies did during the time of sumptuary laws forbidding ostentatious displays of sartorial style, Romano has opted to put this splashy design—hand drawn then digitally transferred to silk and hand dyed—on the inside lining of the sober gray haori.

With Takeuchi serving as translator, the talk in the atelier turns to the two styles of hakama, the divided skirt that men traditionally wear over a kimono: umanori, narrower in the leg and split higher up to accommodate horseback riding, and andon, the wider-legged lantern-style. The education continues as Nakashima describes different dying techniques, and a style of raw-silk fabrication that has earned a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage designation called yuki-tsumugi, in which the silk is harvested and woven by hand and immersed in hot water to make it nubbly in texture.

Rummaging through bolts of material, Romano falls for a refined, azure-color fabric and remembers a kimono he received as a gift; the blue material would make a perfect matching hakama for it. Nakashima, amazed at Romano’s recall of color and detail, marvels, “There are very few who have the kind of eye that Romano-san has.”

The fitting complete, it’s back to Roppongi and to Sushi Nakamura, where Romano is friends with the Michelin-starred sushi chef Masanori Nakamura. “The fish is out of control here, it’s just so good,” raves Romano, admitting he rarely bothers with sushi in America anymore.

When an unusual dish of fermented red uni (sea urchin) emerges, Nakamura explains that the fishermen who catch the urchin do the fermenting themselves. “I like this better than raw uni,” Romano says. “Can I have [the fishermen’s] denwa bango [telephone number]?”

A procession of exquisite dishes emerges from Nakamura’s hands at a relaxed pace: abalone dressed with the dried ovaries of the sea cucumber and lightly grilled Manila clams. “That’s the brilliant thing about Japanese grilling,” Romano comments. “You do it on skewers so you get all of the grilled flavor but none of the char.” Other standouts include beautiful pieces of horse mackerel and slippery Japanese cockles.

Recalling a playful dish he made for Nakamura and his wife when they came to dinner at UST, Romano says, “I made ‘sushi’ with fregola and preserved lemon, bound with avocado puree and put raw tuna on top. His wife said she liked it better than Nakamura-san’s sushi.”

Finally, their appetites sated, Romano and Takeuchi offer thanks to the chef and his staff and head into the Tokyo twilight.

A week later, Romano’s “Summer Preview Dinner” takes place, a seven-course extravaganza that includes white asparagus with smoked salmon coulis and salmon roe; carrot “farrotto” and shungiku (chrysanthemum greens) pesto; roasted eggplant stuffed with sardines from Ishikawa Prefecture; grilled lamb chops; and cherry-ricotta clafoutis.

In an attempt to put into words what Japan has taught him, Romano recalls an emotionally charged chef’s trip to the Tohoku region after the devastating earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in 2011. The idea was for a group of American chefs to offer comfort in the best way they knew how: to feed the refugees. When 2,500 instead of the expected 1,000 guests lined up to sample the chef’s dishes, an announcement was made asking guests to limit themselves in the number of dishes they took. Romano was unaware of the announcement when suddenly guests began passing up his station. Realizing what was going on, he recalls, “I was so emotional I could hardly talk. It was really beautiful.” He adds, “At the center of it is that sense of ‘we’,” the recognition that each person is part of a large whole.” He says, “I try to think about that in my life and adapt it, try to live that.”

Another memorable event came in January. To celebrate Romano’s 60th birthday—an especially auspicious anniversary in Japan known as kanreki—the staff threw him a party, to which he invited about 25 friends from all over Japan. One of them, a sake brewer from Kyoto’s Tsuki no Katsura, brought a large-format bottle of a specially brewed sake with a 60th birthday label attached, as well as a case of two of Romano’s favorite sakes. Also in attendance were three of Romano’s kimono mentors, or sensei. “Half of us were wearing kimono at this party,” recalls Romano, although he had to be careful when dressing for the event since he had to wear a haori from one master, a kimono from another and an obi from yet another.

The celebration led Romano to take stock of his life so far, and reflect on his future. “It got me thinking about what I’m going to do with what I call ‘the final third,’ he says. “I want to spend a lot of time in Japan.”