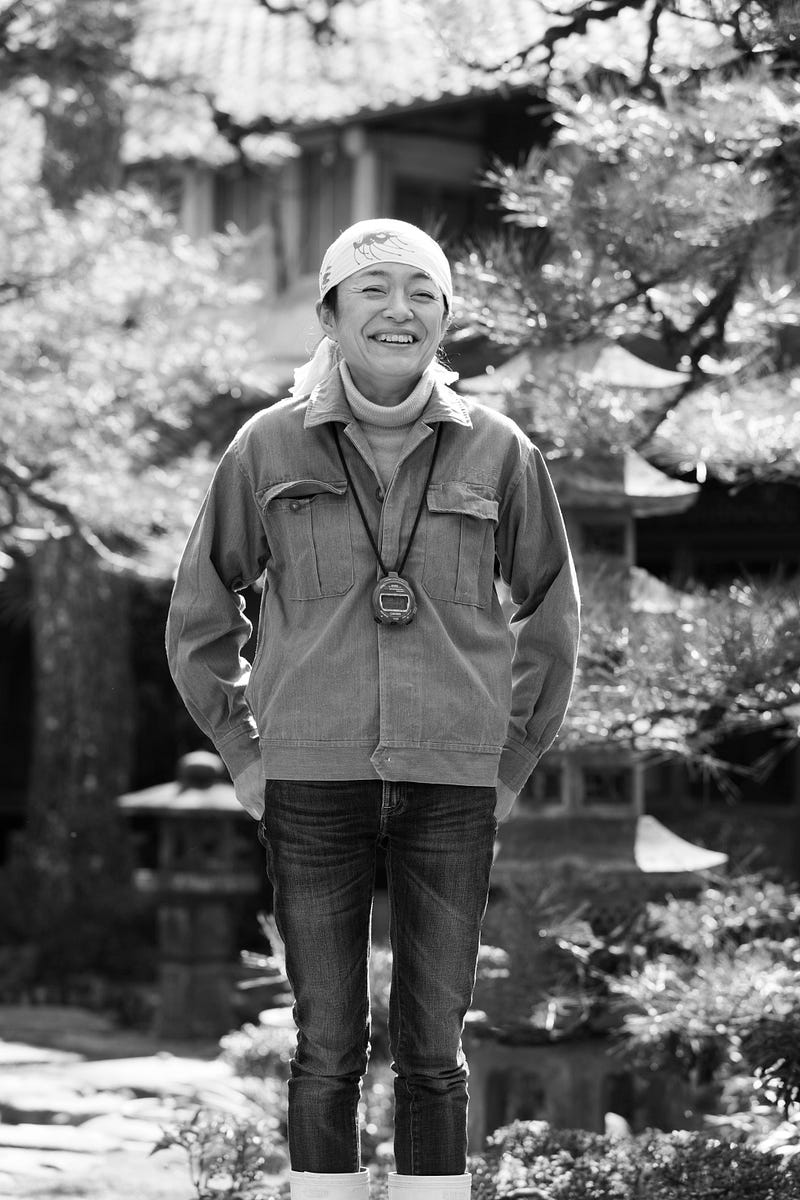

Master Sake Brewer Miho Imada

Of the approximately 1,000 functioning sake breweries left in Japan today, only 23 can say that their master brewer, or toji , is a woman. It wasn’t always this way. According to ancient sake lore women were the first makers of sake, and the earliest sake makers of the Yayoi period (BC 300 - AD 300) were shrine maidens called miko, who brewed the beverage as an offering to the gods, employing a primitive method that involved chewing and spitting rice and letting the body's own enzymes do the work of fermentation. An early proto feminist belief has it that the characters for the word toji, 杜氏, are a corruption of another rendering of toji, 刀自、meaning “madam” or “lady.”

At some point, though, men seized control ; by mid-17th century, sake making — with its punishing hours, laborious lifting, carrying, and mash stirring — was considered a man's job.

Now, the balance is beginning to shift once more as labor shortages, aging brewery worker populations and improved physical facilities and conditions have brought women increasingly important roles in the sake-making process.

Earlier this year, I visited one of the most accomplished and senior among the women toji now working in Japan, Miho Imada of Imada Brewery in Akitsu, a small town on the Inland Sea that's been swallowed by the larger city of Higashi Hiroshima. Slight of build, and possessed of a disarmingly pixieish grin, the 53-year-old master brewer and brewery director has worked long and hard to keep her family's nearly 150-year-old brewery alive. The 22 years that she's been at the brewery — eight apprenticing with the brewery's previous toji , Yasuhiro Kiyotaka, and nearly 14 years on her own — have coincided with Imada Brewery's rise to excellence. The artisanal brewery only produces 65,000 1.8 litre bottles a year, a drop in the bucket compared to large industrialized makers, but it has made its name in America with several soft, clean and beautifully brewed bottles under the Fukucho label: "Moon on the Water" and "Biho" junmai ginjos and "Forgotten Fortune" junmai.

Yet it's only been in the last year or so, says Imada, "that I've really begun to love my work." Before that, she says, it was "agonizing," yet "quitting was not an option. There was no one else to do the work. "Her father, Yukinao Imada, now 80, was growing older, and her brother had opted to become a doctor instead of take over the family business.

"Technically," she explains, I did not have all the skills I needed, and you can not make good sake alone, you have to have a good team. "When those two elements came together, she says," that's when it became really interesting. "

Now, Imada is at the forefront of a golden age of experimentation among sake brewers that is both energizing the world of sake aficionados and the key to saving an ailing industry.

From the zenith of sake consumption in 1975, when over 400 million gallons were consumed in Japan, the brewed beverage's popularity has plummeted, down to 160 million gallons in 2010. In recent years, sales of premium sake have seen a slight upswing, but the decimation of the industry, from 4,000 breweries 80 years ago to about 1,000 operating breweries today, continues.

What small-scale brewers like Imada are doing is playing with the few variables available in a brewed beverage that is made of only rice, water, a type of mold used to facilitate the conversion of rice starch to sugar, and yeast. She's revived a defunct , heirloom varietal of local rice called Hattanso and pioneered a new technique that is a cross between the yamahai or kimoto styles of ambient, or wild yeast fermentation and the more predictable and stable "fast-acting" method of adding lactic acid to the yeast starter to speed the process of fermentation. And, in the prefecture that invented premium ginjo , or delicate, aromatic sake made with highly polished rice, she's bucking the trend by making a beautifully balanced sake that is less polished and more interesting.

Though she had heard about the ancient grain Hattanso, Imada recalls, "there were no seeds available." Then about 15 years ago the local prefectural institution for plant genetics preservation began targeting Hattanso, the oldest and rarest local rice seed, for experimentation, starting with the little bit of the seed that had been preserved. It happened that one year the institute had a surplus of cultivated seeds, and divided it among the growers who were interested.

Back then local sake rice growers were growing non-indigenous Yamada Nishiki rice, considered the king of sake rice varietals for the fragrance and softness of its product. Hattanso, explains Imada, results in a "clear, refreshing sake, very close to the taste of the fish that's caught here in Hiroshima, "and an ideal match with local foods. Now she works with five nearby farmers who grow Hattanso for her, and 25 percent of Imada Brewery's sake are made with the still-rare grain.

For her "Forgotten Fortune" sake using Hattanso, Imada also played with the milling rate of the rice. "Until now, it was all about ginjo," she explains, the premium sakes that are milled to no more than 60 percent of their original size, resulting in a delicate, aromatic sake. Rice polishing technology has become so advanced, she adds, that "where before rice could only be polished to 60 or 70 percent, now it can go as low as 40, 35, even 30 percent . But this 20-year trend has reached a dead end, she believes. "We've overdone it, it's done," she asserts.

"We want to make more fun, pleasurable, creative sake."

By experimenting with milling rates, she's come up with a 75% milling rate for "Forgotton Fortune," which allows for the fullest expression of Hattanso's pure and clear taste.

Imada has also used her hybrid starter technique, which eschews the addition of purchased lactic acid to prevent unwanted bacteria from thriving and resulting in off flavors, yet does not fall prey to the unpredictability of the slower, naturally occurring lactic acid fermentation of the yamahai or kimoto styles. Her secret: the isolation, with the help of the Hiroshima prefectural research institute, of locally produced lactic acid bacilli, which allow her much more control over the taste and aroma of the final product. The result is a less fruity, less " pretty " but more interesting and complex sake that's stable and replicable.

Like a number of women toji , Imada was lured back to the family business by a sense of duty and the hope that there was a brighter future for sake ahead.

After studying law at Meiji University, Imada opted to stay in Tokyo. It was the late '80s, the height of the bubble economy, and she threw herself into organizing kabuki, dance and theater spectacles. The arts were flush with corporate money, and life was a blast. Then the bubble burst, and Imada took note of the fact that the sake her family was selling in Tokyo at the time was, as she tells me sotto voce , since her father is sitting with us, "was bad, really bad.” She had noticed that in Tokyo, the two or three super-premium sakes available were selling well, while the rest of the industry was dying." I felt a responsibility, and I realized that if we wanted to continue, " she concluded, "we had to make really good stuff."

To her shock, upon her return she was met with open arms by the entire Hiroshima toji establishment. Most of her dai sempai, or her extreme seniors, were over 70. They had the know-how to make beautiful sake but no one to pass this knowledge on to. "Whatever I wanted to know, they taught me," she recalls. "They'd invite me to their brewery and say, ‘How many days can you stay? Let's arrange it.’ They showed me everything.”

Perhaps because she's never felt discriminated against as a woman, she says, today she treats other women as she was treated:. As equals to their male counterparts "When I visit another woman toji , it's because I like what she's making, not because she's a woman, "Imada says.

When she returned home in the early '90s, though, the industry was in the doldrums, the boom in shochu (the national distilled spirit made with sweet potato, barley and the like) was just beginning and for her it was a time of learning, researching and thinking about how to make a good product. That period also coincided with the deregulation of laws governing liquor store sales and rice growing, which helped encourage experimentation and give birth to the artisanal sake industry.

Today, Imada Brewery, like many small breweries in Japan, exports a small percentage of its product abroad, and counts on the growing interest in sake internationally to jump-start sales at home. By all indications, that is starting to happen. Meanwhile, Imada continues to experiment: with Hiroshima Prefecture's newest type of yeast, with a two-year, bottle-aged vintage sake, and with one sake made with a particular strain of yellow mold-inoculated Hatannso starter that is typically used for shochu making rather than sake. The result, which she shared with me but is not yet for sale, is a delicious, pale yellow Chablis-like sake that is the perfect complement to Hiroshima's celebrated oysters.

Although Imada, her parents and their small team (two full-time male workers and three part-time seasonal workers, two of them women) still operate on razor-thin profit margins using 150-year-old equipment, she displays a hard-won measure of confidence and hope for the future. "Sake," she says, "the real thing, that is — is really getting interesting."

Read it at Medium