Bon Yagi: Emperor of New York's Japanese East Village - Part 2

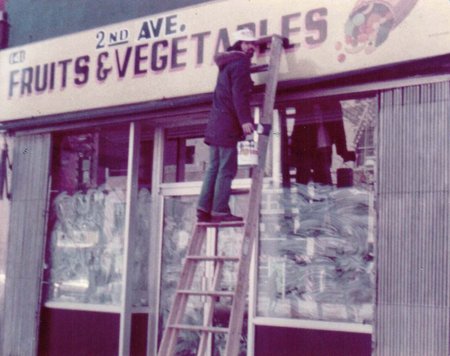

Yagi painting the sign for his Second Avenue fruit and vegetable store.

It was a rough neighborhood, rife with drug dealers and squatters. Yet Yagi says, “Jewish people started here, and Polish and Ukrainians, and then the Japanese. Everybody was accepted, and we never felt strange.” St. Mark’s Church, nearly at the center of his restaurant galaxy, was for a time the burial site of Commodore Matthew Perry, whose tall ships opened Japan to the west in 1854. Plus, notes Yagi, “East,” or higashi, describes Japan. “That’s why I opened all my restuarants here,” he says simply.

Yagi figured that in Japan, people his age were working 50- or 60-hour work weeks, and if he just worked like them, “one day maybe I’ll be the front runner here—I didn’t hesitate to work long hours.”

He got to know a chef at the Empire Diner, the iconic Tenth Avenue art moderne watering hole that stayed open round the clock and attracted a bohemian crowd. By the early 1980s, Yagi had saved enough money to lure the chef away, and opened his own 24-hour-diner on Second Avenue in the East Village.

Called 103 Second Avenue, it, too, became a hot spot, a regular for artists Keith Haring and Andy Warhol. Haring regularly covered the black walls of the bathroom with graffiti, and Yagi, unaware of it’s potential future value, says, “I used to erase it.” He adds, “My employees were all gay and I sold coffee for seventy-five cents, or a dollar-fifty for unlimited refills. John Belushi would come at midnight and loved Sloppy Joes. Madonna used to come before she was famous, too.”

The stars had no idea that the diner they loved, decorated like an understated Japanese establishment in warm wood floors and wooden tables, was run by a Japanese man. Foreshadowing his continued relative anonymity, Yagi says, “I didn’t want anybody to know.”

His stealth “Japanese diner” gave way to his first real Japanese restaurant in 1984, Hasaki, a sushi restaurant on East 9th Street named after the small town in Chiba where his father was born. The underground sake bar Decibel followed in 1993, and Sakagura in 1996. Yagi’s empire building was underway.

His daughter Sakura attributes Yagi’s success to his insatiable curiosity and appetite for work . “As a self-employed person, he’s always on it,” she observes. “There’s never a moment he’s off, and he doesn’t hesitate when there’s a problem to be solved.” In addition to overseeing his 13 restaurants, he owns and manages several apartment buildings, is the New York agent for Toto and at one time was also president of a beer exporting company.

When Yagi decides on a new restaurant concept, his daughter notes, he travels through Japan doing research, decides what to focus on, and finds people to implement his vision. And, she adds, “He’s never afraid to ask questions,” a trait that was embarrassing to her when she was younger, but which she has come to appreciate.

At 67, Yagi shows no sign of slowing down. He plans to expand the business, says Sakura, likely in Japan. But he’s also turned his thoughts to the humanitarian concerns that have marked his career in New York. As chance would have it, he was downtown for both the 1993 below-ground bombing of the World Trade Center and for the September 11, 2001 attack. In 1993 he was on the 87th floor of the World Trade Center, visiting the Hokkaido Takushosku Bank when the underground bomb was detonated. On 9/11, he was with Sakura at the immigration offices nearby the trade center. He took his daughter’s hand and walked her back to the safety of the East Village through Chinatown. Shaken, he took the attacks as a wake-up call to perform an act of Zen self-discipline to honor the dead. As an end-of-year symbolic cleansing, he decided to give up something he loved—sake—and did not imbibe it again for 10 years, until the day his son turned 21.

He was one of several community leaders who started New York City’s akimatsuri fall festival in 1990, and is currently leading the effort to repair a statue of Shinran Shonin that surived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and now stands in front of the New York Buddhist Church. Drawing his roster of restaurants into his charitable activities, he hosts a yearly dinner for Nikkei seniors at Shabu Tatsu.

Yagi with a framed fan given to him by his great uncle Daihachi, with the inscription ware koukaisezu, or “live with no regrets,” top, and the inscription ichinichi ichizen, “one good act per day,” at bottom.

Through a lifetime of bold entrepreneurialism and constant activity, Yagi has created a microcosm of Japan within New York City, introducing the food-scapes of everyday Tokyo to locals more familiar with pizza and bagels. For his “last achievement,” Yagi has his sights set on importing a more spiritual, or cultural Japanese asset to New York: He wants to start a non-profit devoted to the Japanese principle of ichinichi ichizen, or “one good act per day.” Since he shows no sign of slowing down, it’s unclear when he will launch the non-profit, but Yagi envisions it as yet another way of making the city a better place.

“It’s very Japanese, and something I grew up with,” he says. “It’s not meditating,” he explains, “but improving things, through even the smallest of acts.”

© 2015 Nancy Matsumoto