JANM Photo Exhibit: Two Views: Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank

Ansel Adams, Calisthenics, Manzanar Relocation Center, 1943. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The 1942 incarceration of people of Japanese descent in America and Canada following the bombing of Pearl Harbor has been portrayed in scholarly histories, works of art, and the cinema. Yet comparisons of the Nikkei experiences in the two neighboring countries have been rare to non-existent. The upcoming exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), Two Views: Photographs of Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank, will provide the context for just such a comparison.

Ansel Adams, the widely revered photographer of Yosemite and the West, visited and photographed the Manzanar prison camp and its residents in California four times in 1943 and 1944. Leonard Juda Frank, then Vancouver’s most successful commercial/industrial photographer, was hired by the British Columbia Security Commission (Canada’s equivalent of the U.S. War Relocation Authority) to document the forced removal of residents of Japanese descent from coastal British Columbia.

The exhibition, organized by the Nikkei National Museum (NNM), includes 40 of Adams’s Manzanar photographs and 26 prints by Frank documenting the uprooting of over 21,000 of their Canadian counterparts. Manzanar was one of ten U.S. concentration camps that held over 110,000 prisoners; Japanese Canadians were imprisoned in a dozen camps located in the interior of British Columbia with some families sent to sugar beet farms in the province to the east, Alberta.

Frustrated at being too old to fight for his country during World War II, Adams jumped at the chance to do his part and document the prisoners at Manzanar when his friend Ralph Merritt, the prison camp’s director, invited him to visit. His beautifully composed and printed portraits of inmates portray them in their vocations as farmers, seamstresses, nurses, or scientists; the photographs are often imbued with a sense of optimism.

In June 1944, Adams published a book on Manzanar containing 64 of his photos and a text he penned himself, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans. Some praised him for his moral courage while others, revealing the racist undertones in American life, vilified him for sympathizing with the enemy. Over the years, critics have viewed his Manzanar photographs in widely differing ways: as either an attempt to justify the government’s unconstitutional wartime removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans, or a championing of prisoners’ dignity and perseverance in the face of adversity.

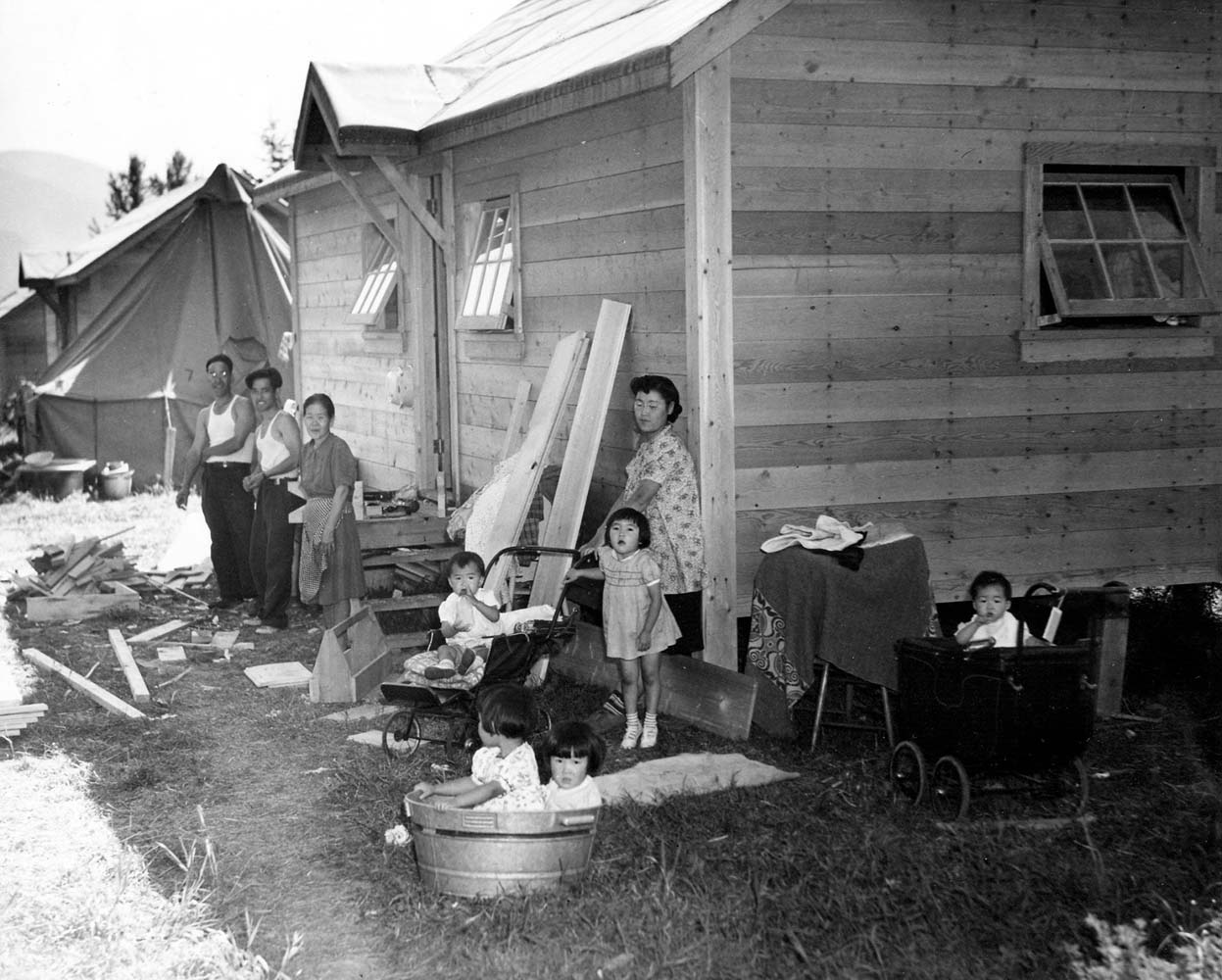

Leonard Frank, Family at Slocan / New Denver? Eastwood Collection JCNM 1994.69.4.16.

Frank’s photographs, by contrast, focused on buildings and structures of internment camp sites in British Columbia as well as road construction sites and Alberta sugar beet farms, not the prisoners themselves. At once more clinical and more disturbing, they depict the shuttling of nameless human beings through a bureaucratic system. Frank is mostly known today for his documentation of daily life on the British Columbia coast and formerly untouched landscapes, yet his ability to capture exquisite shifting light effects made him more than a photographic surveyor. He left a legacy of approximately 50,000 images of British Columbia coastal landscapes in the B.C. archives.

As a German-born Jew and naturalized Canadian who experienced exclusion and discrimination during World War I, says Grace Eiko Thomson, founding Executive Director/Curator of the Japanese Canadian National Museum (JCNM, now the Nikkei National Museum), “We have to wonder what his thoughts were in visiting these sites.” To call Frank’s images “clinical,” she adds, implies a lack of point of view, and is too simplistic; the very fact that Frank’s photographs bear no sign of interaction with the prisoners, she believes “produces interaction between the viewer and the stark images.” Knowing that during World War I Canadian residents of German, Ukrainian, and Slavic origin were imprisoned under the same War Measures Act that enabled the Japanese internment1 camps, Thomson adds, underscores this tension.

By contrast, she notes, Adams’s photographs, depicting happy faces directly engaged with the photographer’s camera, can lead viewers to the conclusion that the “evacuation” as it was euphemistically termed, “was the right course of action” for the American government to take.

Though produced by the Nikkei National Museum, the traveling exhibition’s first incarnation was in 2003 at Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver. Bill Jeffries, then Director/Curator of Presentation House Gallery, seized on the opportunity to include the WWII treatment of people of Japanese descent as part of a three-room exhibition. The third room documented the Irish experience of arriving at Canada’s “Ellis Island” (called Grosse-Île), which operated from 1832 to 1937. Those images, by Canadian photographer Eileen Leier, examined a preserved site of national importance—similar to the World War II prison camps of the American interior that have been turned into historic sites open to tourists.

Grace Eiko Thomson suggested JCNM’s collection of Frank photographs as a complement to Leier’s work and Adams’s Manzanar photographs, and a three-part exhibition was born. Thomson’s first thought, she says, was that the show would be “a great opportunity for a long overdue discussion of Canadian and American experiences of internment.” The addition of Frank’s photos, adds Jeffries, “was not a big leap for me—even the Main Street courthouse in Vancouver is built on land seized from Japanese Canadians.”

“Presentation House Gallery is not a collecting exhibition space, so when the 2003 exhibit closed, Bill Jeffries offered to sell the Ansel Adams Manzanar prints to JCNM at minimal cost,” says Thomson. She in turn recommended that the Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association purchase the prints and donate them to the museum on the condition that the prints, along with the Frank photographs, be packaged as a traveling exhibition by JCNM toward educational purposes.

For many viewers familiar with the Nikkei incarceration experience in the U.S., the facts of the Japanese Canadian experience will come as a shock. Comparisons between the two governments’ treatment of their West Coast Nikkei residents in the 1941 to 1945 period, says Jeffries, “do not flatter Canada.”

For example, while the exclusion order was rescinded in the U.S. on January 2, 1945, and most of the U.S. prison camps had been shut down by the end of 1945, in Canada, says Thomson, Japanese Canadians were not granted their freedom until 1949, “close to four years after the end of the war.” Spurred by racist slogans such as “Not a Japanese from the Rockies to the Sea,” the government gave the released prisoners only two choices: to settle east of the Rockies or to “return” to Japan, which for Canadian-born prisoners was an alien country and hardly home to them.

While some more fortunate Japanese American incarcerees returned to the West Coast to find their homes, farms, and properties intact, protected by loyal friends, in Canada the prisoners’ personal property and possessions were “confiscated by the government and sold without the owners’ consent,” says Thomson. “Throughout the war, they were forced to live on the proceeds from the sale of their property, leaving many impoverished when too elderly to rebuild their lives,” she adds.

Her own family, after being uprooted in 1942 from the west coast of British Columbia to Minto Mines, a mining ghost town in the province’s interior, relocated to rural Manitoba after its release from prison. When restriction of movement was lifted later in 1949, the family moved again, to Winnipeg. For Thomson, who was fifteen years of age by then, the adjustment was a “traumatic” one, she says, involving daily brushes with one form of discrimination or another. It wasn’t until Canada’s redress campaign in the 1980s that she began to seriously study internment. She learned that as in the U.S. the internment of Japanese Canadians had “little if anything to do with ‘security risks’,” but followed a long history of discriminatory practices against them.

Her belief, says Thomson, is that by documenting the Japanese Canadian and Japanese American shared experience of injustice, “Two Views offers the opportunity not only for discussion of artistic/photographic interpretations, but also a chance to compare the Nikkei experiences in Canada and the U.S., from incarceration to redress settlements.”

At their Saturday, April 9th talk at JANM, the two curators will detail how the “warm and fuzzy” image that many Americans have of Canada is mostly a post-war phenomenon, Canada now having become, says Jeffries, “as internationalized as any other country.” He adds, “The American camp experience, for all its abuses, may seem slightly more benign when the treatment of Japanese Canadians is offered up in comparison, and it is a history that very few Americans know anything about.”

Note:

1. In Canada, the word “Internment” was originally not used as the government could not legally ‘intern’ Canadian citizens under the Geneva Convention. Instead, prisoners were “detained.” However, the government now uses the term internment as a reality. The debate over terminology that has taken place in the U.S., with Densho’s preferred term being “concentration camp,” has not occurred in Canada.

* * * * *

Two Views: Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank

February 28 – April 24, 2016

Japanese American National Museum

Two Views: Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank examines the forced incarceration of citizens of Japanese descent who were living in the western coastal regions. Ansel Adams’s photographs reveal the harsh daily life and resilience of the 10,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, while Leonard Frank’s images capture the movement of Japanese Canadians through British Columbia’s bureaucratic systems. Two Views is a traveling exhibition organized by the Nikkei National Museum.