‘For the Culture’ Is a Joyful Celebration of Black Women and Femmes in Food

Pastry chef and writer Klancy Miller was raised by two food-loving parents. Her mother collected and cooked from all of Julia Child’s works and took her to Paris for the first time when she was 15, helping to seed in her a love for France and its culinary traditions. But the life in food and hospitality that Miller later forged sent her in a different direction, one that connected her with the African diasporic community and role models closer to her own identity.

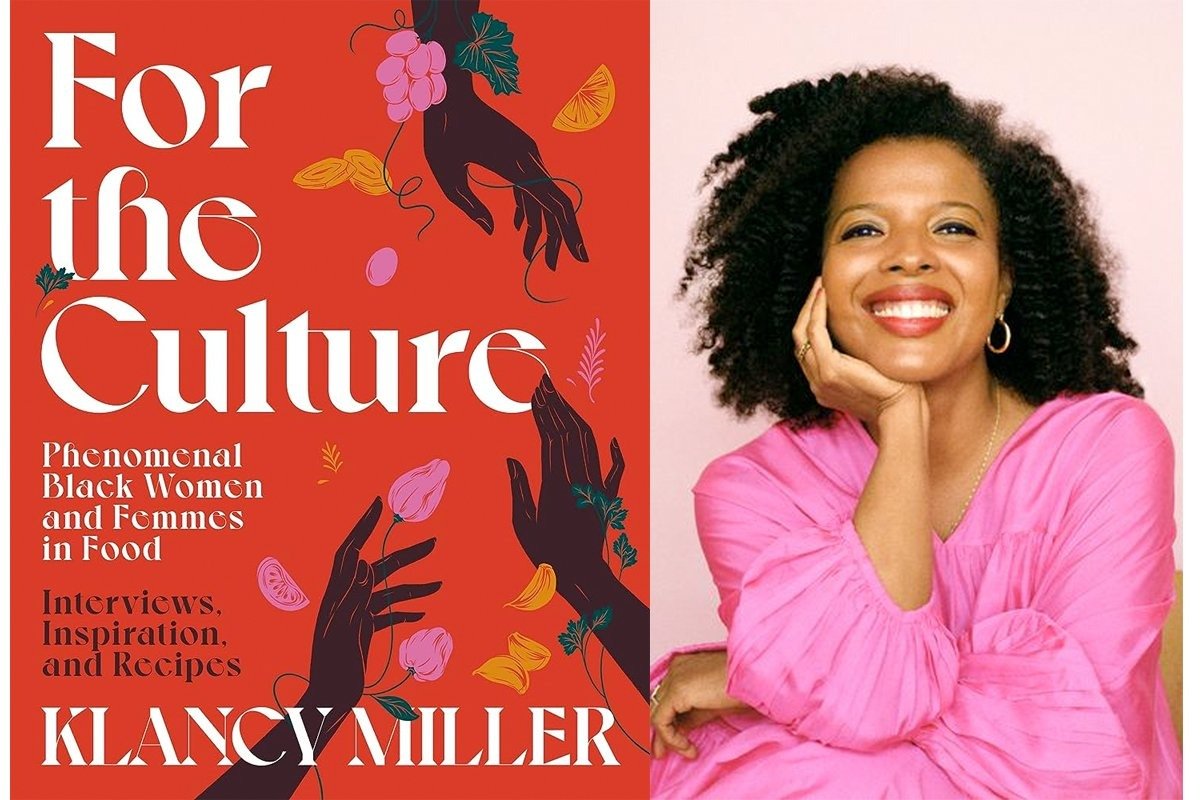

Miller’s new book, For the Culture: Phenomenal Black Women and Femmes in Food, features 66 interviews with Black women in food, wine, and hospitality and 48 recipes collected from her subjects, plus vibrant illustrations by Sarah Madden and lavish photography by Kelly Marshall. Though the book is a joyful celebration of Black women and non-binary femmes and their achievements, it does not shy away from addressing hard truths about racism, money, and mental health.

“I do feel strongly that it’s important to see yourself and see different options for yourself and people you can relate to.”

Miller’s varied interests—in African American and Middle Eastern history, film, and culinary arts—eventually led her to this project. After attending Columbia University and working in the Middle Eastern division of the American Friends Service Committee, she landed an apprenticeship at Philadelphia’s Fork Restaurant, a job that inspired her to learn more.

She earned a pastry degree from Le Cordon Bleu in Paris in 2001, then worked as an apprentice at the city’s Michelin-starred Le Taillevent before embarking on a stint developing recipes at Le Cordon Bleu. After returning to the U.S. in 2004, she worked as a freelance writer, baker, and supper-club host, among other things, and devoted a long stretch of time to getting to know people in the food world, establishing the beginnings of her own community.

Miller published her first book, Cooking Solo: The Fun of Cooking for Yourself, in 2016. It assured readers that they were worthy of delicious solo meals and that mastering cooking for one’s self naturally segued into cooking for and entertaining others.

In January 2021, she founded a biannual print magazine called For the Culture that featured Black women and femmes in food and wine—and served as a template for what would come to be the book.

In the book, Miller pays homage to the grandes dames of African American culinary history, from cooks and authors Edna Lewis and B. Smith to culinary anthropologist Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor. She also pays tribute to “all the Black women and femmes who steward the land, feed us, and bring us together with food and wine,” including farmer Leah Penniman, chef Mashama Bailey, culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, and television host and producer Sophia Roe.

Miller hopes this book will provide the kind of information, advice, and “sisterly insights” she wishes she’d had access to as she was coming into the world of food and food media.

Can you tell me how this book came about?

Around 2016, I was having conversations with Kerry Diamond at Cherry Bombe, and we talked about doing an all-Black issue of the magazine. There were some obstacles, though, and then a friend suggested, “Why don’t you do it yourself?”

I do feel strongly that it’s important to see yourself and see different options for yourself and people you can relate to. So, in late 2019, I launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money to create For the Culture magazine. I raised $40,000 on Indiegogo from 700 or 800 people. There were two women in North Carolina, Jenelle Kellan and her baker friend Keia Mastrianni, who organized bakers to do bake sales and raised close to $10,000.

“I feel like everyone in the book is a multi-hyphenate. There is such a wealth of talent, so they’re not just doing one thing, but several things in a really dynamic way.”

How did you decide who would be included in the book?

I wanted to center these women’s stories and bring them to the fore. They’re people I admire, people I’m curious about, and also people I have a personal connection to, who I see at events, whose pop-ups I go to, and who are at various stages of their careers. I didn’t just want people at the height of their careers, but people of different ages, and people throughout the diaspora—in the Caribbean, on the African continent, and in Europe. I want there to be a global feel to the book.

You open the book with short essays on five iconic trailblazers—Edna Lewis, Barbara Elaine Smith, Leah Chase, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, and Lena Richard—who, you write, “serve as our collective North Star.” How did you choose these particular women?

I consider them culinary matriarchs and felt there was no way I could do this book without paying tribute to them, though there are many more. I couldn’t just say their names; there had to be more substance. And since they are no longer alive and can’t be interviewed, I included them in personal essays.

One of the striking things that so many of the women and femmes you profile have in common is that they are multi-hyphenates—entrepreneurial people who are wearing many hats at once, whether it’s as chef, baker, sommelier, activist, podcaster, author, or artist. Is this what it takes to make it in hospitality today?

I feel like everyone in the book is a multi-hyphenate. There is such a wealth of talent, so they’re not just doing one thing, but several things in a really dynamic way. Honestly, even outside of hospitality, and certainly within, it does take wearing more than one hat, because the world we live in today is really expensive, particularly in cities like New York.

It also speaks to the creativity of people in this book. Many are drawn to speaking, whether on a podcast or elsewhere, or working with their hands making food or baking. It’s what’s required today in a practical sense, but I think people also want to express what they have inside themselves.

What are some other qualities your subjects have in common?

Being really nimble, smart, and flexible. Realizing that sometimes you have to change. They are all self-starters; they just initiate, make the move, say they can. Being a self-starter is absolutely the through-line.

“In the Black community, and likewise in the queer community, that feeling of people needing each other is a human truth, a beautiful commonality.”

You also focus on both financial and mental health as keys to a successful life. A piece of advice that came up a number of times was, “know your worth.” How do you see people helping each other develop better negotiating skills, financial knowledge, and the confidence it takes to ask for more money?

I actually feel that a lot of people are pretty transparent if you ask them questions. I try to be, especially when it comes to writing books, because it feels like an area that’s almost cloaked in secrecy, and this goes beyond race. We’re all doing the same thing so why can’t we be transparent?

I wanted to ask [my subjects] about mental health because I do think the hospitality industry is kind of terrible on that. It’s so physical, the hours are long, and workplaces can be chaotic. I wanted to know, how are you taking care of this part of your life?

One answer is so simple: When you’re feeling creatively stuck or burnt out, it’s almost always because you haven’t been living your life. A remark from Kia [Damon, chef and founder of Kia Feeds the People] really made an impression: “Go out and get ice cream or go to a museum with friends. Just enjoying yourself is a major part of life.”

The women you feature come from around the globe—Jamaica, Ghana, Morocco, and throughout Europe—so they don’t all share the specific trauma of slavery that African American women do. Was that difference apparent in any way?

I am African American, and my great-grandparents were enslaved, and there were enslaved people in my family. I don’t know what it’s like to not have that as part of your family history. But I do think that the nature of colonization and race relations means that even if you didn’t have enslaved people in your family history, you can probably relate to some of the dynamics across the diaspora, the many points in common.

Jamila Robinson [former food editor for the Philadelphia Inquirer, current editor in chief of Bon Appétit] makes an interesting point: “A lot of Black women have ‘imposter syndrome,’ which I think is nonsense. When you feel like you don’t belong in a space, that’s not ‘imposter.’ That’s not being welcomed in the room.” Do you think Black women often confuse the two?

I’ve never related to imposter syndrome because I’m not trying to be anyone else; I’m here doing what I do. I do love Jamila’s turning it on its head and looking at it from a different angle. That’s brilliant, and I think that not being welcome in the room is equally prevalent.

To build on this quote of Jamila’s, when you are “othered” or not at the table, you have to build your own community; you have to rely on your friends and allies, who might not always look like you. That sense of community is a really prevalent theme in the book. In the Black community, and likewise in the queer community, that feeling of people needing each other is a human truth, a beautiful commonality.

“One of the reasons I wanted to write it was to feel more connected to my community . . . It has definitely contributed to my own personal growth. I’m learning how to be more supportive, to be a better community member.”

Are you seeing the falling off in interest in diversity and equity that others are right now?

Yes, for sure—there is definitely a loss of interest. On the positive side, I do think there was progress made during that brief window of time [after George Floyd’s murder], and we’re starting to see the results of that progress—for example: my book and a lot of other great books coming out by Black authors. I don’t know if in my adult life I’ve seen so many cookbooks by Black authors come out in such a short period of time. In 2020, it felt like wow, it’s a whole new world.

But the [reason] was very sad. It was hard to digest: “I’m getting an opportunity based on somebody being murdered; this is horrible and absurd, and he should still be alive.” But that was six to 12 months max that it lasted, and now DEI programs are being eliminated. It was a finite moment in time. But a lot of seeds were planted, and we’re beginning to see them blossom.

How has writing this book changed you?

One of the reasons I wanted to write it was to feel more connected to my community. I wanted conversations with people I admire, to learn from them and to be able to call them colleagues and, in some cases, friends. It has definitely contributed to my own personal growth. I’m learning how to be more supportive, to be a better community member.

It’s also given me permission to just do whatever I want to or need to do. There are so many women whose paths have changed since I interviewed them; it’s really fascinating. They’ve switched paths, or quit their jobs, so I feel empowered to make whatever tweaks I need to my own path. We’re all works in progress, and I admire the comfort with the unknown that these women exhibit.

Read this article online at Civil Eats.