What the World War II Japanese American Experience and Linsanity Have in Common

|

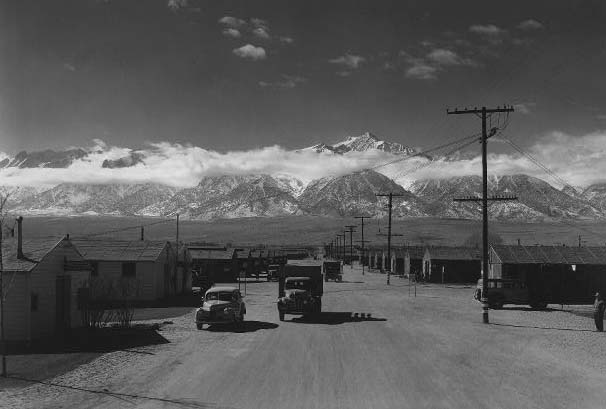

| Ansel Adams photograph of Manzanar, 1943, Library of Congress |

I was excited to learn that an American literature teacher and journalist in Shanghai, Britte Marsh, is having her tenth grade literature class study my essay on the World War II Japanese American prison camp Manzanar. Britte’s lesson plan is intriguing: to have her international school students read the young adult novel The War Between the Classes by Gloria D. Miklowitz and supplement that reading with my 18-part series.

The combination is a good one because the book is about a high school teacher who devises a game designed to explore the themes of racism, classism and sexism. He divides his students into four artificial classes, or socioeconomic strata, each designated by different-colored arm bands. This new order upends the natural hierarchy of the class: rich white students become the poorest of the poor and must bow and scrape to their superiors, the minority students. The protagonist, a Japanese American girl, also becomes aware of her family’s incarceration in a World War II U.S. government prison camp.

Britte wrote to me, “Together with the novel, I anticipate that your series will encourage my students to connect the dots between stereotyping, racial prejudice, media and ownership of familial heritage.” Out of her class of 13 tenth graders, only three had heard about the forced removal and imprisonment of West Coast Japanese, perhaps not surprising since none of them are Americans. One boy who was familiar with this chapter of American history was a Japanese student, again not surprising, since the topic is of great interest to the Japanese, who are probably on the whole more aware of the story than the average American.

The emails from Britte came at an interesting time, during the weeks leading up to the 70th anniversary of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, which authorized the imprisonment of West Coast Japanese Americans as a “military necessity.” Just as this essay on Executive Order 9066 that I wrote for The Daily was posted, the Asian American American Journalist Association’s (AAJA) listserve was exploding daily with fresh comments about Jeremy Lin, the American-born Knicks basketball sensation who seemingly came out of nowhere to galvanize both his injury-ridden team and the world. Every day a fresh example of racial stereotyping, if not racism, was unearthed, in headlines, on Twitter, and by sports commentators. AAJA was admirably on the ball in spotting and drawing attention to these, and even issued a media advisory (since the AAJA site is temporarily down, I'm linking to member Lia Chang's site, which has the advisory posted) with tips on what is acceptable coverage of Lin and what is not.

Although global attention has been mostly admiring, and angled as the classic underdog story of an unknown breaking out to become a star, I couldn’t help but notice some parallels between Linsanity coverage and the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. For one thing, it’s hard for some sports journalists and fans to see Lin as the American that he is. Just as the Nisei, or American-born Japanese Americans, were during World War II, he is considered foreign. Someone like Alex Rodriguez is not defined as a Dominican immigrant, even though he lived in the Dominican Republic for part of his childhood. A first-generation Irish or German American pro athlete would be even less susceptible to such perceptions.

The AAJA media sheet advised reporters and editors, “Jeremy Lin is Asian American, not Asian…Lin’s experiences were fundamentally different than people who immigrated to play in the NBA…to characterize him as a foreigner is both inaccurate and insulting.” Reading this for me evoked the cognitive dissonance of seeing prison camp photos filled with high school-aged Japanese Americans recreating the rituals, fashions and hairstyles of the all-American high school—the yearbooks, glee clubs, bobby socks and baseball teams—only behind barbed wire.

A lot has changed since those long ago days, and Jeremy Lin’s story is proof of that. Yet his story also reminds us that some things are still the same.