A Farmer and a Baker Talk Heritage Grains

|

| Mark Stambler's miche and sourdough. |

The two humans, farmer Mai Nguyen and baker Mark Stambler, gave a lecture at the recent L.A. Bread Festival, held at the city's recently revamped Grand Central Market.

Mai, a perky Vietnamese American with large horn-rimmed glasses who farms on five acres of land near Ukiah in Mendocino County, grows four different heritage grains. Her favorite is California's Sonora soft white spring wheat. Adapted from grains brought to Mexico in the late 1600s by Jesuit priests, it made the country's first wheat (instead of the usual corn) tortillas possible. By the early 1800s it was widely planted in California, which was then still part of Mexico. Sonora wheat is considered California's first landrace wheat, meaning it's a grain selected not for ease of production or length of shelf-life, like most modern hybrids, but for taste and texture.

|

| Farmer and baker. |

Mai explained that the revival happened roughly seven years ago, thanks to the efforts of Glenn Roberts, the San Diego native and founder of Anson Mills; Sonoko Sakai, whose organization Common Grains focuses on reviving heritage grains in Southern California; and the Whole Grain Connection, devoted to the proliferation and availability of sustainably grown whole grains. Despite this ferment of whole grain activism in the state Mai says that not only is it still hard to come by Sonora soft white seeds, finding quality seeds can be even more difficult.

As a baker, Mark likes Sonora for its softness and buttery scent, both of which make it well suited to pastries and cakes. Because it doesn't have a high gluten content it is ideally suited to making tortillas, he says. For bread making he mixes it with white flour to get a loaf with good "oven spring." He also knows how he'll have to adjust his recipe depending on where in the state the wheat was grown.

The most common question he hears about baking with heritage grains, said Mark, is how recipes written for store-bought flour from commodity grains must be adjusted. To him, it's simple: add more water if the dough is too stiff, and more flour if it is too loose.

|

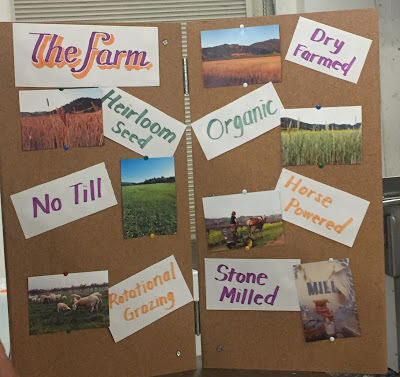

| Agriculture as practiced by Farmer Mai. |

Long cultivated in temperate to hot and dry regions of Mexico, Sonora wheat is well suited to similar conditions in the Ukiah valley, Mai notes. The grain's drought resistance is key to her success, because she dry farms, meaning that she relies only on rainfall to water her crops. She also practices no-till farming to prevent soil erosion, increase its water retention and maximize its microbial diversity. She uses a horse-drawn plow, which in addition to providing a way better farming experience than riding a tractor, reduces her carbon footprint and prevents topsoil compaction.

One of the challenges of being a small-scale grain farmer in an agribusiness-dominated commodity crop country is that it's hard to find appropriate-sized equipment. Mai was able to track down a small combine from a farmer in the Sierras. Though built for grain trials and nursery harvesting, it suits her needs just fine. Her purchase reminded me of a similar find that I wrote about in this Civil Eats article: the 62-year-old small combine that upstate New York farmer Ashley Hollister had to travel all the way to Ohio to collect.

Combines take care of all aspects of the harvesting process, including reaping, threshing and winnowing, and their three-in-one utility is where the name "combine" comes from. Done by hand, as it once was, the process is laborious to a crazy degree.

Mark has tried it himself. Growing the wheat is the easy part, he says. When his 10' by 6' plot was of wheat was tall enough, he cut the heads off with scissors. But the threshing, or removing the outer hull of the grain, took grit. Thrashing at his plastic bag filled with wheat with a stick didn't work so well, nor did smashing it with bricks. It wasn't until he ran over the wheat with his Honda Civic that he finally started getting somewhere. Separating the wheat from the chaff, or winnowing, was equally frustrating. He set an electric fan in front of a bowl and tossed the threshed wheat in the air so that the chaff blew away and the heavier wheat fell into the bowl. But he needed to do this repeatedly, and then still spend an entire afternoon picking through the wheat to finish the task. A day's work netted him about four ounces. The lengths DIY-ers will go to to live the manual labor life of our forebears!

For a busy farmer like Mai, the combine she bought is a must-have. It also beats out what she calls "the catastrophe that was last year's harvest." She hired the one person in her region with a mobile combine and was dismayed to learn she was to be the "guinea pig" for his new machine. The result was watching 20 percent of her crop scattered in the field. She plans to contribute the combine to a seed equipment cooperative she belongs to. Members have been scouring old barns across the country to find small-scale equipment that has fallen out of use as farmers have scaled up. The plan is to officially incorporate the group as as a seed cleaning facility, where, says Mai, "we'll be able to clean seeds for consumption and reproduction," as well as save them for future heritage grain farmers.

So having her very own combine has made her a happy camper and farmer. Good luck, Mai!

So having her very own combine has made her a happy camper and farmer. Good luck, Mai!