Uka Sake: Closing the Circle on a Trans-Pacific Rice-Growing Legacy

Grain harvesting at Koda Farm, circa 1930. Photos courtesy of Koda Farms.

Rice farmer Ross Koda’s immigrant grandfather Keisaburo was larger-than-life, a pioneering rice farmer known throughout the California agricultural community in the early 1900s as “The Rice King.” He was an energetic entrepreneur who won big and gave back generously, to the industry and to his home prefecture in Japan.

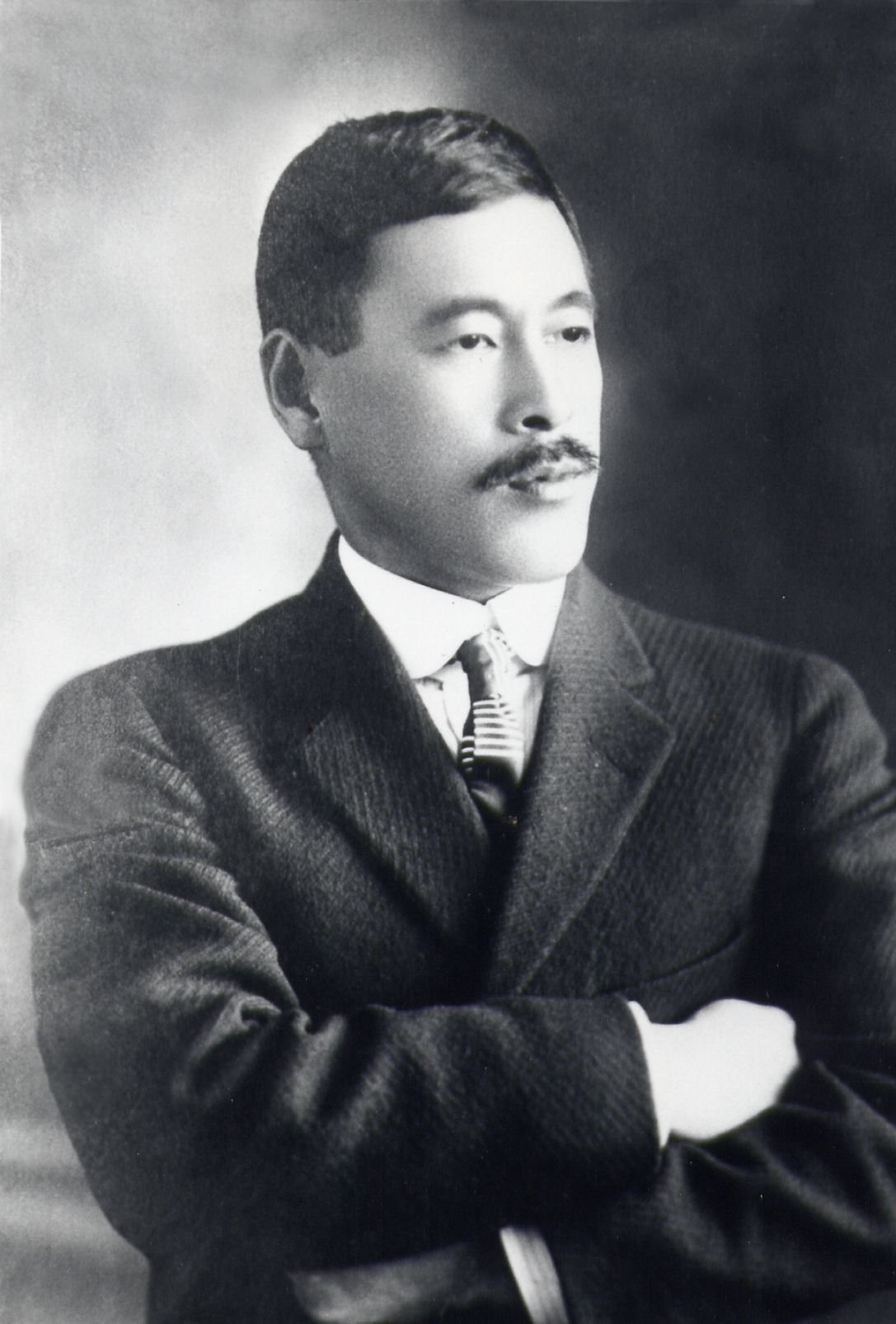

Portrait of Keisaburo Koda, circa 1900.

After the family’s unconstitutional World War II incarceration devastated the business, Ross’s father Ed and his older brother Bill and their families labored to bring the business back to prosperity. They made their Kokuho Rose medium-grain rice, Sho-Chiku-Bai glutinous rice, and Blue Star mochiko rice flour staples in every Japanese American home, including mine.

Keisaburo Koda, right, with custom harvester Bill Bell.

But the family history in rice stretches back further, to Japan. There, Ross and his sister Robin’s samurai great-grandfather turned to milling and selling rice when the regional lord he served fell from power. Another samurai ancestor went on to plan and develop rice fields. With such illustrious ancestors, Ross thought about what he could do to contribute to the family legacy.

The answer lay in his fields, specifically the CCOF-certified organic fields of Kokuho Rose 55. the tasty, proprietary trademarked strain developed in the early 1950s at Koda Farms. KR55 —yet another major milestone achieved during the tenure of Bill and Ed Koda—was developed by Hughes Williams, a well-known rice breeder who at the time was employed by the Kodas. It is a medium-grain improvement on Calpearl, the ubiquitous, high-yielding California short-grain rice, descended from seeds brought from Japan by turn-of-the-century immigrants.

Kokuho Rose 55 in flower. .

The development of a line of organic rice products in 2004, meanwhile, was one of Ross’s achievements, involving the implementation of a separate processing system and traceability from seed to store shelf.

An egret flies over a Kokuho Rose 55 field. Organic growing practices have made Koda Farms fields a haven and waystation for migratory birds.

After he began exporting the line to Japan, one buyer there told Ross that he was using it to brew sake. Here was an idea; perhaps brewing sake with Kokuho Rose could be Ross’s “contribution to our family’s history in rice,” he told me during our interview. He checked out local California breweries as possible collaborators, but either they were too small and focused on their own production, or they were giant industrial brewers who had no interest in a boutique project.

The flagship Uka Black junmai daiginjo.

But Ross didn’t just want his sake brewed with the family’s organic rice, he wanted sake brewed near his grandfather’s birthplace in Fukushima. It would be a way of connecting his generation with his grandfather’s and “closing the circle.” He wanted to name the brand “Uka,” which means “emergence,” as in a butterfly emerging from a chrysalis. A close family friend, Hideo “Uncle Hank” Ide, offered to help search for an appropriate brewery.

Inside the original, water-powered Koda rice milling facility in Iwaki City, Japan. L-R, Ross’s cousin Shinichi Koda, who still operates a rice retail shop; Ross; the rice miller; Ross’s Uncle Eiji; and Uncle Hank Ide.

Every brewery Uncle Hank approached declined his proposal except one: Ninki Shuzo in Nihonmatsu, Fukushima. Yujin Yusa, owner-brewer at Ninki, says, “After hearing about Ross’s roots and Keisaburo’s life story, I felt I wanted to make Ross’s wishes come true.”

So Yusa began brewing trials. Accustomed to the local Fukushima rice Chiyonishiki as well as Gohyakumangoku, native to Niigata, Yusa says that mastering the brewing process using organic Kokuho Rose 55 took some time. “Compared to Japanese rice, it’s longer and harder, and we did not know its characteristics until we brewed with it,” he says. By the third tank he felt he was able to brew on a par with his other sakes. Although the brewery ferments some of its sake in wooden kioke tanks, Yusa opted for the quick-fermenting sokujo method for the three different Uka junmai daiginjos on offer: the classic ginjo-style Black Label, the much drier Uka Dry, and a sparkling sake. All feature a rice milling ratio of 40 percent.

n/naka’s Devin Davenport poured Uka Dry sake for us when we visited. the restaurant in December. Photo by Nancy Matsumoto.

The first batch arrived in the United States in September 2019, shortly before Covid-related supply chains problems hit global shipping. Now, with its fourth season of brewing underway, the Uka line is available in 14 states and expanding, says Michael John Simkin, Uka’s national director of sales and marketing. To import the product, Ross has founded a separate company, Omurasaki, a reference to the giant purple butterfly pictured on the Uka labels and its theme of transformation. Uka has found a place on the menus of a handful of destination dining restaurants, including Michelin-starred restaurants n/naka kaiseki restaurant in Los Angeles, and Single Thread in Healdsburg, California.

Some have questioned the wisdom, in these greenhouse-gas-emissions-aware times, of the large carbon footprint created by sending California rice on a round-trip to Japan, returning as sake. Ross says this is a situation that is constantly on his mind. Starting with his fourth round of brewing in 2023, instead of sending the genmai, or whole grains to Japan, he found a specialty rice miller in Sacramento. By taking the grains down a 40 percent milling ratio before shipping, he reduced his carbon footprint by 60 percent.

The importance of the Fukushima location to his family story, as well as Ninki Shuzo’s history and location, Ross believes, make shipping California rice to Japan in return for brewed sake a worthwhile tradeoff. “To me, it’s a very special place, located at the base of Mt. Adatara, with water that’s been filtered (through the volcanic mountain rock) for 40 years,” he says. Although Yujin Yusa started the brewery in 2007, he brings with him the legacy of his family’s more than 300-year-old brewery Okunomatsu Shuzo.

Another reason to stick to this arrangement, Ross adds, is that “it’s a kind of symbiotic relationship. With sake consumption declining in Japan, export markets are an important part of the lifeblood for toji-driven artisanal craft breweries.”

Keisaburo, his wife Yoshie, and their three children, Florence, Ed, and Bill, circa 1930.

Discussions are ongoing with Ninki Shuzo about how to expand the Uka line as well as the reach of organic Kokuho Rose 55, says Ross. But equally meaningful to him is the spread of Uka’s deeply personal message: “That we are a nation of immigrants, and we all have ancestors who deserve our gratitude.”

Some updates on Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake:

Michael and I are delighted that our book, Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake: Rice, Water, Earth, has been longlisted in the drinks book category of the UK-based Andre Simon Book Awards for 2022!

I had fun collaborating with Toronto chef Eva Chin of Avling Brewery and New York chef Emily Yuen from Brooklyn, on a sake-and-beer tasting dinner at Avling earlier this month. It was the first time for me to do sake and beer together. As part of the talk portion of the evening, it was interesting to chat with Avling founder Max Meighen about how the two drinks are similar and how they differ. Both have enjoyed a renaissance in the craft, with sake’s boom now where beer was several decades ago.

Next up, Michael and I will be giving a virtual sake book talk for the Japan America Society of Chicago on February 16. Hope to see you there!

If you liked reading this post, click on the pink box above or below it and subscribe to get future posts in your inbox!